In the 19th century, one out of every four hardwood trees in eastern North America was a chestnut. You’ve heard “The Christmas Song” (www.carols.org.uk/the_christmas_song_chestnuts_roasting.htm)—chestnuts were a favorite food not only for humans, but also for wildlife. Wood from chestnut trees was used to make everything from barns to fine furniture. But by the middle of the 20th century, hardly a chestnut remained standing, over four billion trees felled by the chestnut blight.

Four billion! The only survivors were in west coast populations not reached by the fungal pathogen responsible for the blight.

Since 1928, when Dutch elm disease was first reported in North America, it has killed over 40 million American elm trees. Though not as completely devastating as the chestnut blight, Dutch elm disease has had at least as dramatic effect on urban forests. Although Dutch elm disease hasn’t killed every last American elm, planting programs and homeowner preference made elms the dominant tree in many cities and towns. Elms were a favorite of homeowners and urban foresters alike because of their stately stature, wildlife value and ability to withstand compacted soils and air pollution. When Dutch elm disease struck, some cities lost huge fractions of their trees. New Haven, CT, garnered the nickname of “Elm City” because of its first-in-the-nation public planting program. It still sports that moniker even after Dutch elm disease killed more than ninety percent of its elms. Nicknames and street names in many cities across the country are nearly all that remains of the elm’s legacy.

Since 1928, when Dutch elm disease was first reported in North America, it has killed over 40 million American elm trees. Though not as completely devastating as the chestnut blight, Dutch elm disease has had at least as dramatic effect on urban forests. Although Dutch elm disease hasn’t killed every last American elm, planting programs and homeowner preference made elms the dominant tree in many cities and towns. Elms were a favorite of homeowners and urban foresters alike because of their stately stature, wildlife value and ability to withstand compacted soils and air pollution. When Dutch elm disease struck, some cities lost huge fractions of their trees. New Haven, CT, garnered the nickname of “Elm City” because of its first-in-the-nation public planting program. It still sports that moniker even after Dutch elm disease killed more than ninety percent of its elms. Nicknames and street names in many cities across the country are nearly all that remains of the elm’s legacy.

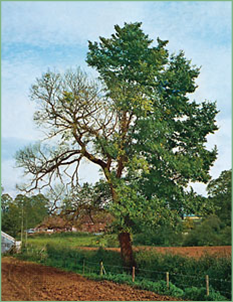

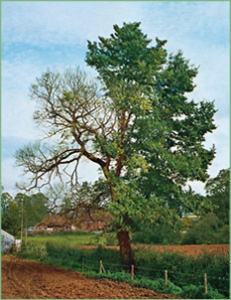

Components of our forests have also come under attack more recently. Sudden oak death is a fungal disease that has killed thousands of oak trees along the West Coast. The sudden oak death pathogen has been found in nursery plants shipped from California to many other locations, including the Carolinas (whereupon the suspect plants and any others they may have infected were summarily burned by USDA and state officials). This is not just a threat to oak trees, as hundreds of different plants have been shown to be susceptible. The disease is not thought to be currently established in the U.S. outside of California and Oregon (it is also in the U.K. and continental Europe), but if it does show up here, it could drastically alter our forests and landscapes.

Closer to home, our native hemlocks have suffered greatly from infestation by an insect, the woolly adelgid. Hemlock is a fairly common landscape plant, but the impact of the adelgid infestation is most seen in the mountains, where it is quickly altering the composition of forests from Georgia to New England.

Another insect, this one a tiny beetle, is leaving a swath of dead trees along the coast of the southeastern U.S., from Mississippi to North Carolina. The red bay ambrosia beetle is only about as big buy viagra com as Lincoln’s nose on a penny, but it carries a fungus deadly to red bays, sassafrass and other members of the laurel family. Red bay ambrosia beetles were first discovered near Savannah less than a decade ago. Since then, the rapidity of its spread and the destruction it has caused have been amazing.

There are numerous other threats to our landscapes and urban forests (emerald ash borers, long horn beetles, exotic invasive plants, climate change, etc.), but I want to discuss what lessons we can learn from the blights of the past to minimize the detrimental effects of future blights.

One thing we can do is to hedge our bets, so to speak. Sudden oak death is an exception, but most diseases and insect infestations are quite limited as to the host plants affected, impacting only one or a few closely related species. By planting a great diversity of plants, if blight strikes one type of plant, the entirety of our landscape won’t be destroyed.