Summer’s here now officially according to my calendar, although for us, it seems to have started a couple of months ago.

Summer’s here now officially according to my calendar, although for us, it seems to have started a couple of months ago.

Some of our ornamental plants disappear in summer. They follow a pattern the reverse of most of essay on addiction our hardy but tender plants—those that die back to the ground after we get a hard freeze. For instance, the foliage of spider lilies (AKA hurricane lilies, Lycoris radiata and other species) withered a few weeks ago, and the plants will remain hidden until the flowers appear as summer wanes and fall begins.

Most plants should be thriving this time of year. If the plants in your landscape are not living up to your expectations, it may be time to lower those expectations. Many plants don’t seem to grow much until they have had sufficient time to become established. Trees and shrubs, especially, may take a few years before they start to grow in earnest. During the establishment period, most of the growth is in the root system, and we don’t see it.

If your plants aren’t relatively new, it might be time to see if there’s a reason for the plants’ poor performance. Water, too much or too little, is responsible for more problems in the garden and landscape than any other factor. The immediate symptom of over-watering is usually wilting, with leaf yellowing, browning and dieback following. Drought can also produce wilting—if the roots are deprived of oxygen from saturated soil they will cease to function and the leaves will not get sufficient water. Excessive moisture often leads to disease problems; fungal diseases, especially, thrive with ample moisture and humidity. Don’t assume your irrigation system is working perfectly when problems arise—pull the mulch away and get your hands in the soil to check moisture levels.

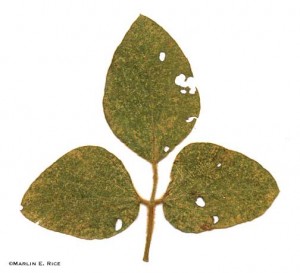

Usually if critters (mites, slugs, insects, squirrels, rabbits, deer) are feeding on your plants, you’ll see the damage they leave behind or the critters levitra prescription on line themselves (although it may take magnification to see the smallest mites and insects). [Look for more on this topic next month.]

Usually if critters (mites, slugs, insects, squirrels, rabbits, deer) are feeding on your plants, you’ll see the damage they leave behind or the critters levitra prescription on line themselves (although it may take magnification to see the smallest mites and insects). [Look for more on this topic next month.]

Diseases can be less obvious. Many produce lesions on leaves, but some are difficult to diagnose. Sometimes the only symptom will be wilting or dieback. I find tomatoes to be the most difficult plants to diagnose–there are viral, bacterial and fungal diseases that all produce quite similar symptoms.

If your plant is growing slower than it should or producing insufficient flowers and fruit, and the problem is not suboptimal water and light conditions, it might be time to have the soil analyzed. By having your soil chemically analyzed, you’ll know what to apply to get pH and nutrient levels optimal. Optimal soil chemistry means healthier plants, less waste (and less expense and potential run-off pollutants). Clemson Extension offices will accept soil for testing—for a modest $6, you’ll find out which fertilizer is best for what you want to grow and how much of it you’ll need, and the same for lime.

The only tricky part about having your soil tested is knowing how many tests you need. Most average size lots will require at least two tests. Any area in which a problem is occurring, whether it’s a dead spot in the lawn or a pecan tree that’s not bearing, should be tested separately—sample the healthy part of the lawn separate from the problem spots. Also any place where the soil color and texture are obviously different should be sampled separately. Vegetable gardens, where the soil has been amended should be analyzed separately from the surrounding lawn.

For each area to be tested, you need to submit a pint or more of soil. The submitted soil should be representative of the area of interest—this means you should take a number of subsamples, at least six, and combine them to make up the sample for submission. For example, for a small front lawn, select eight spots spread around the lawn. At each spot, collect one-quarter of a cup of soil, place it into your bucket, and move on to the next spot. The soil from all eight spots will comprise the one pint sample for submission. The soil too should be collected from the depth at which most of the roots will grow. For lawn grasses, this means from the surface to a depth  of 3–4”. For most other situations, including trees, shrubs, landscape beds and vegetable gardens, aim for the surface to a depth of 5–6”. The easiest way to do this, unless you have a soil corer, is to make a V-shaped pit with a trowel to the appropriate depth and then scrape the sides of the pit to collect the quarter cup of soil. The soil should be free of roots or stones or anything else that’s not growing medium. It should also be dry or nearly so—if you collect wet soil, let it dry for a day or two before taking it to your county Extension Office (Richland: 900 Clemson Road, 8:00 a.m.–4:30 p.m., 865-1216; Lexington: 605 W. Main Street, 8:30 a.m.–5:00 p.m., 359-8515). You can also take in cuttings and photos of your problem plants.

of 3–4”. For most other situations, including trees, shrubs, landscape beds and vegetable gardens, aim for the surface to a depth of 5–6”. The easiest way to do this, unless you have a soil corer, is to make a V-shaped pit with a trowel to the appropriate depth and then scrape the sides of the pit to collect the quarter cup of soil. The soil should be free of roots or stones or anything else that’s not growing medium. It should also be dry or nearly so—if you collect wet soil, let it dry for a day or two before taking it to your county Extension Office (Richland: 900 Clemson Road, 8:00 a.m.–4:30 p.m., 865-1216; Lexington: 605 W. Main Street, 8:30 a.m.–5:00 p.m., 359-8515). You can also take in cuttings and photos of your problem plants.